In a recent escalation of border tensions, firefights broke out along the Pakistan-Afghanistan border late on Saturday, with Taliban-led Afghan forces seized multiple Pakistani Army outposts along the Durand Line, including in the volatile Kunar and Helmand provinces, Afghanistan’s Ministry of Defense said. The clashes, still ongoing, are the latest flare-up in a cold war that has smoldered for more than a century; a war of correction, over a line neither nation chose.

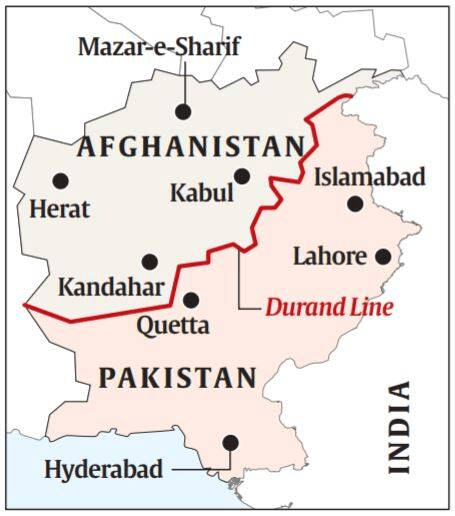

The Durand Line was never drawn for the Afghans split on either side of it. In 1893, the British diplomat Mortimer Durand carved a 2,640-kilometer frontier through Pashtun and Baloch lands to keep British India safe from the rival Russians. The deal was made under occupation and pressure, signed by a monarchy who had British guns to their face, and never ratified by any actual Afghan assembly. When the British Empire vanished, Pakistan inherited the line as its western border, but Afghanistan did not inherit consent.

That single decision tore apart whole nations. Pashtun and Baloch tribes that once traded, married, and fought together found themselves living under two opposing governments. The new Pakistani provinces of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) and Balochistan were never “foreign” to Afghanistan; they were extensions of its linguistic and cultural soul. Even today, Afghans see the Durand Line as an amputated part of their identity.

For the Punjabi Concentrated Government of Pakistan, the line is settled law. However, for Muttahid Afghanistan and the restive region Balochistan it stays an open wound.

Tensions over the frontier have always flickered, but the past year pushed them into open fire. Islamabad accuses Kabul of harboring Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) insurgents who strike Pakistani targets from Afghan soil. Kabul counters that Pakistan’s decades of interference, from backing Al Queda, to shaping post-2001 governments, created the very instability it now blames on Afghanistan.

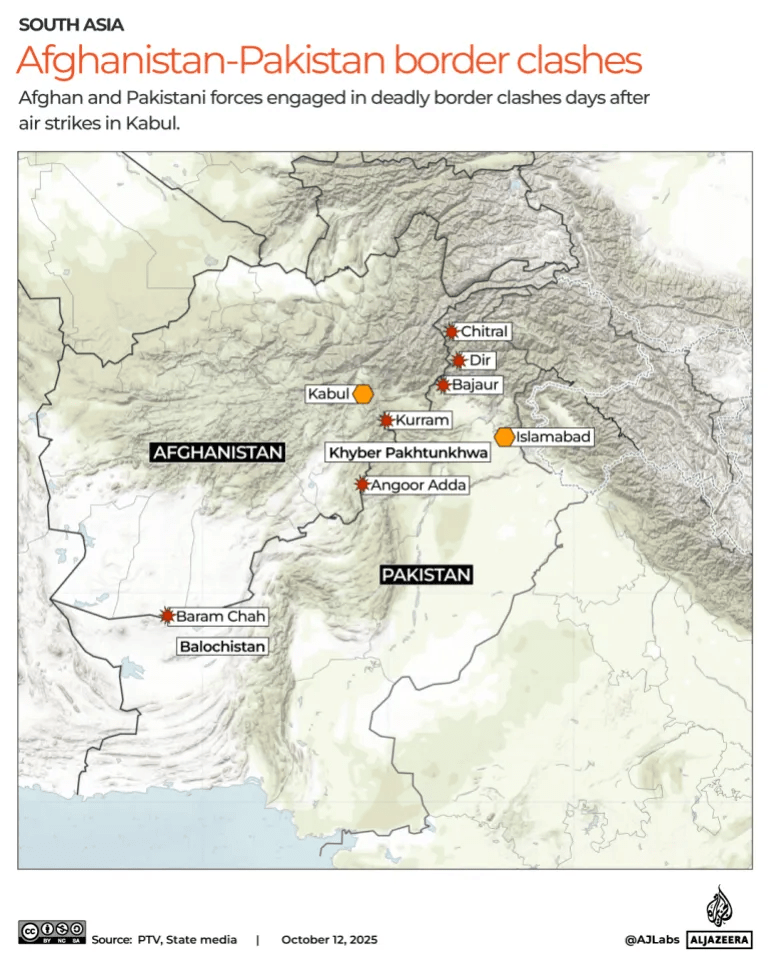

This autumn, the uneasy balance snapped. After a wave of resistance operations by the TTP inside Pakistan, the Pakistani Air Force launched cross-border missile onslaughts inside sovereign Afghan territory, claiming to target militant bases in densely populated parts of Kabul. For Afghanistan’s rulers, that was a disgusting violation of it’s sovereignty, something Pakistan seems to specialize in. Afghan national defense forces hit back across the frontier, overrunning several outposts of the Rawalpindi regime and releasing footage of captured positions. The fighting has since spread along multiple sectors of the border.

What makes this clash different from past skirmishes is afghani posture. For the first time in decades, Afghanistan’s government, for all its controversies, is asserting control over its territory rather than turning the other cheek. It’s a statement not just to Pakistan, but to history, the days of treating Afghanistan as a client state are ending.

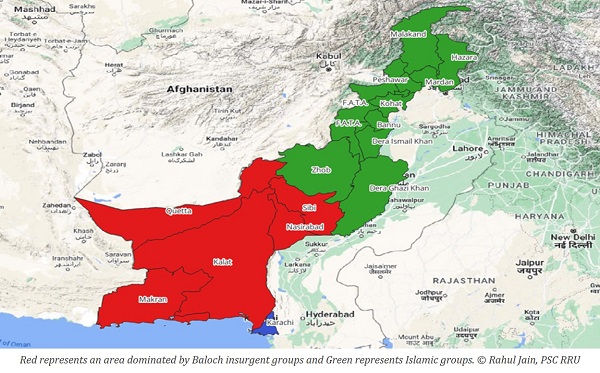

However, the war for sovereignty is not fought by Afghanistan alone. Along Pakistan’s western rim, two long-simmering movements; one in Balochistan and another in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa; have been fighting their own battles for outright independence.

In Balochistan, the Baloch Liberation Army (BLA) and related groups have waged a decades-long insurgency, indicting the Punjabi establishment of exploiting the region’s huge mineral wealth, whilst keeping its people in poverty. From natural gas to copper, the province’s resources feed Pakistan’s economy and light up Punjabi streets, all while Balochi towns remain among the poorest in the country. The Liberation Army’s attacks on infrastructure and military convoys, though condemned, come from a much more deeper demand, an end to the Punjabi Occupation.

Farther north, Pashtun nationalist movements in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa have freed KPK from centralization by Islamabad. Some seek greater provincial autonomy; others, full sovereignty in order to reach the concept of a greater Pashtunistan, a homeland for the millions of Pashtuns divided by the Durand Line. Although these movements share little organizational unity, they still share a major grievance.

Neither side can win a war that began with a pen stroke in a colonial office. Afghanistan cannot erase the Durand Line without international consensus, and Pakistan cannot defend it from the people who want it gone on both sides of the line. Pakistan faces an insurgency they cannot bomb into silence and economic crises they cannot afford to deepen.

A route to peace begins not with maps but with mutual acknowledgment: that the border’s legitimacy is not merely a legal matter but a human one. The people of Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa deserve to be part of any solution, not just its casualties.

Joint border commissions, shared customs zones, and transparent trade corridors could turn the frontier into an asset. Economic interdependence is not a cure-all, but when goods and people can move freely, violence has less space to grow.

But both me and you know that real reconciliation is impossible as long as decision-making about the frontier remains in the hands of Islamabad’s military establishment. For decades, Pakistan’s western policy has been written by punjabi generals rather than local civilians, designed to control territory rather than understand it. As long as the army treats Balochistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and the Afghan borderlands as security zones instead of human societies, every promise of peace will collapse under the weight of occupation by pakistani bureaucracy and barracks alike.

Lasting stability will only come when the command structure steps back, either by leaving the iranic lands completely, or giving the people sufficent autonomy.